Thought Leadership

Falling transfer fees to be a marker for football’s post-Covid-19 austerity era

12 MIN READ

Thought Leadership

Inspired by what you’re reading? Why not subscribe for regular insights delivered straight to your inbox.

It’s clear that Barça won’t let me leave for an apple and an egg,” said backup goalkeeper Jasper Cillessen in the summer of 2019, as the club reportedly sought a buyer who could pay his €60m release clause. “The market is really crazy. Honestly. It’s true they are paying incredible transfer fees for players that we all know aren’t worth that much.”

That window was yet another peak for transfer spending in Europe’s ‘big 5’ leagues, with nearly €5.5bn paid in fees. Cillessen himself was sold for a reported €35m valuation, a climbdown from €60m, but still an obscene value to many for a player who had clocked just 48 hours of on-field work in three years at Camp Nou.

A year on, these figures feel sharply out of touch with the global mood brought on by the Coronavirus pandemic. Before we even consider the impact that the collapse in economic activity will have on football clubs’ ability to pay transfer fees, it is hard to imagine that total spending figures on footballers in the billions will sit comfortably alongside government spending of similar magnitudes on Coronavirus measures.

It is therefore a time of deep introspection for the sport. Reflecting on how and why the transfer window has grown, the importance of it to clubs of all levels, and how we can expect transfer strategy and spending to change in the future will reveal what’s keeping technical departments and ownership groups up at night.

Football’s all about money now – and has always been

“£170 grand for Colin f****** Todd?!”

“Correction – the almighty Colin Todd, the best technical footballer in the country”

“And a salary of 300 quid a week?! You can’t pay a footballer that!”

“That’s the way things are going Uncle Sam. Football’s all about money now”

No doubt written with tongue firmly in cheek – and with a healthy benefit of hindsight – Peter Morgan’s dramatisation of an exchange between Derby County owner Sam Longson and manager Brian Clough in the 2009 adaptation of David Peace’s The Damned United perfectly captures the long-held incredulity of spending figures in football.

The numbers seem quaint now, but Todd’s transfer in February 1971, which made him Britain’s most expensive defender, would have brought out similar emotions to those we felt when Harry Maguire became the latest player to break that record last summer. In fact, Todd’s fee would have amounted to approximately 35% of Derby County’s turnover, far in excess of the roughly 12% of revenue that Maguire’s £80m fee cost Manchester United.

This difference reflects the fact that although Maguire cost 450 times more than Todd, Manchester United’s income today is around 1,500 times more than Derby County’s in the 1970s. Transfer fee inflation is underpinned by revenue growth, and while a multitude of factors come into defining the final agreed price between buyer and seller, one of the remarkable aspects of the transfer market is that, in relative terms, fees have remained more or less constant.

In the Premier League era, net transfer spending as a proportion of the twenty clubs’ turnover has consistently hovered around 15 percent. The fees paid for individual footballers expected to have a transformative impact have, especially in the financial fair play era, generally constituted around 20% of revenues. So when Valencia paid a club-record €25 million fee for Joaquín in 2006, his fee was in relative terms similar to that of Gonçalo Guedes’ €40 million price tag in 2018 – just over 20% of revenues in both cases.

In our experience, clubs do not make these choices consciously; this is an example of market forces finding a ‘natural’ level. To clubs wondering how much fees will fall in the summer of 2020, however, these rules of thumb provide a forecasting model. If revenues fall by a quarter, then fees should fall by at least the same magnitude, likely more in the event that cash balances are depleted, too. Clubs in leagues such as the Dutch Eredivisie and Scottish Premiership, who derive upwards of two-thirds of revenues from gate receipts and commercial income, are likely to be harder hit in their ability to pay.

The transfer trickle down effect

Traditionally, there have been only three revenue streams you could trust to consistently deliver money to a club: broadcast, matchday, and commercial. However, in recent times transfer revenue has become a legitimate fourth income stream, and for some clubs outside of the major leagues, it’s even the primary source of profit that keeps them afloat.

Many smaller clubs have found it increasingly hard to grow the size of traditional revenue buckets, as global fan attention has turned to the big five leagues. Clubs have been effectively constrained by the size of their domestic economy, with only Danes taking an interest in their domestic league, or Bulgarians in theirs (and both taking an interest in, say, the Premier League).

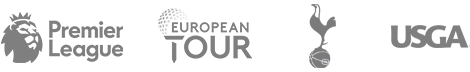

Today, for every euro that a top division European club outside the ‘big five’ earns from one of the three traditional income streams, they receive 41 cents in transfer income – almost twice as much as these clubs collectively receive from UEFA prize money and distributions. This is just the average, too. Figures from UEFA show that teams in Croatia’s top division earn €3 for every €1 in traditional income.

While it is true that two-thirds of the big five leagues’ spending is between teams in these leagues, this excess one third still amounts to over €1.5 billion per season, distributed to, in most cases, poorer clubs in leagues like Croatia. Some might see it as a sticking plaster that papers over the inefficiencies with which these leagues are run, but either way the transfer market has become something more than a means to buy and sell players; in many cases, it’s a club’s entire business model.

Smaller leagues will face enough problems when they emerge from the Covid cloud; they now have to closely monitor the resumption of the big five leagues, too. The extent to which these big leagues resume spending over the coming transfer windows will dictate the financial struggles of these smaller clubs. Assuming that things are quiet for a period following resumption of play, these clubs will have to seriously consider their business models, particularly if they haven’t set aside some of their transfer windfalls for a rainy day.

Value is all around, if you know where to look

While businesses faced with recession in any other industry invariably cut their workforce, football clubs have much less flexibility. Clubs still need to field eleven players each match, fill a substitutes’ bench, and have sufficient players waiting on the sidelines in the event of injury. Plus of course they must employ backroom and front office staff to keep the business operating. It would be absurd for a law practice to cull staff and then employ the same quantity of lower-paid alternatives, but this is the scenario football clubs face if they wish to survive.

As such, being able to identify undervalued players becomes more important than ever in a post-Covid world; in financial terms, this means finding a value arbitrage between the players a club sells and the players they buy.

In practice, this means identifying traits in players that other clubs, for whatever reason, don’t think are correlated with success. The market for players is sufficiently efficient that the next Lionel Messi is unlikely to be found playing in the Finnish second division (the world’s 157th-best league according to our models, in case you’re wondering), but there are still countless players whose salaries and transfer fees do not reflect their ability.

These needn’t necessarily be ‘diamonds in the rough’ like a Jamie Vardy in the lower leagues, either; Tottenham Hotspur’s purchase of Son Heung-min or even Ajax’s purchase of Dušan Tadić were examples of teams acquiring players for less than most other equivalent players, despite relatively hefty fees in absolute terms.

There are systematic over- and undervaluations, too. Take, for example, players who have recently been part of relegated teams. The focus in talent ID on player mentality means that these individuals are often tagged as ‘losers’, unable to prevent their team from failure. By contrast, those with recent winners’ medals – often regardless of the competition – are blanket classified as ‘winners’, and therefore desirable in the market.

These, however, are examples of under- and overvalued career traits. Our analysis of players bought from relegated teams suggests that they’re available for as much as 50 percent less than a comparable player from a non-relegated team. It is this type of alternative thinking that has served Liverpool well, with Georginio Wijnaldum, Xherdan Shaqiri and Andrew Robertson purchased from teams that went down.

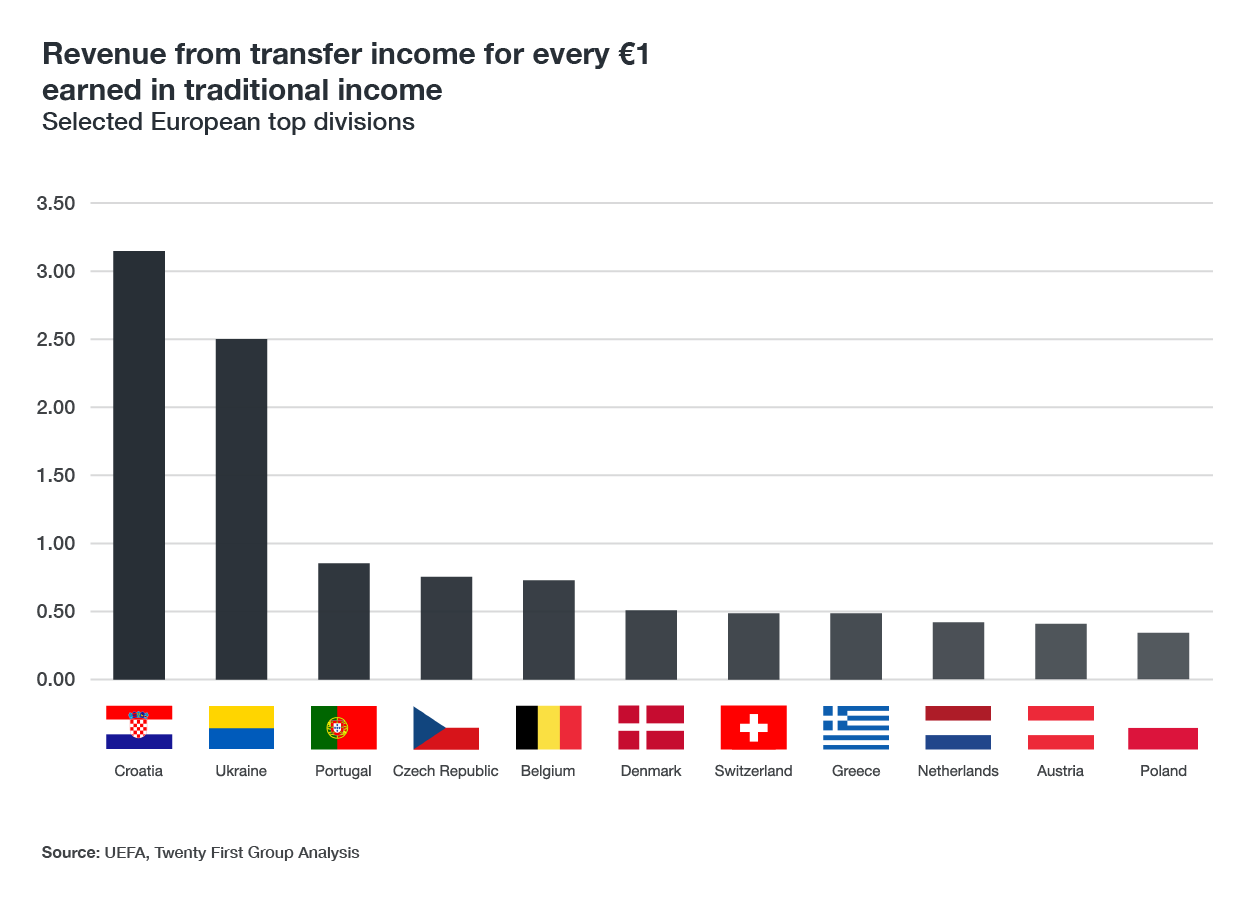

In some cases, there are entire leagues that are under- or overvalued. Our World Super League, which uses machine learning to rank over 4,000 teams globally in one ‘league table’, highlights teams, and by extension players, who are performing at a level far above those teams and players with bigger budgets and salaries. However, perceptions about the overall quality of their divisions end up muddying perceptions about individual teams and players.

Slovan Bratislava, for example, play in the unfashionable Slovakian Super Liga, but are rated as being as good as many relegation-threatened teams in the big five leagues. Our models suggested key striker Andraz Sporar as being a €20m player, but in the end he was sold in the winter for just €6m to Sporting CP in Portugal. The relatively low fee was still a record sale for the league, no doubt boosting the mood of Slovan’s CFO.

With scouts grounded, there are only two ways clubs can differentiate themselves in talent ID processes: throw more resources at video scouting, or get smarter with data. With budgets squeezed, and the diminishing returns of getting eyes on games, effective use of analytics will unlock access to undervalued players for many teams.

Fortunately for some clubs, there is no undervalued talent quite like academy talent. The pressures of modern day football, and the financial cliff edges that exist at every level, mean that coaches invariably prefer to select tried-and-trusted players over kids coming out of the academy. Nobody gets fired for buying IBM.

Many clubs, however, will be reluctant to spend transfer fees at all this summer, let alone the wages that come with peak-age players – so they must turn to their academy. Fortunately, the risks of playing youth are overstated: our analysis of teams that have substantially increased under-21 playing time within their first team have on average seen no adverse impact on results.

Indeed, some of the most successful talent developers of the 2010s only became so after they nearly faced financial ruin. Southampton, Feyenoord, Lyon, and Schalke are all renowned for the players they have produced in the last ten years, but these were players who may never have been given a chance had their clubs not been running out of money. In addition to favouring those clubs, and specifically the technical departments that can leverage data to unearth value, the Covid crisis will also reveal the academies that had been operating effectively without the opportunity to prove it.

Taking advantage of the misalignment of price and worth

Cillessen’s complaints last summer raised a point about what a player is worth, which is a concept football has never truly separated from the actual fees paid. “He’s worth whatever a club is willing to pay for him” is an oft-repeated line. The market is the market.

In a post-Covid world, however, club ownership is going to demand a sharper focus on return on investment from its recruitment department. Exit markets for €35m mistakes will be scarce. These departments, which have historically only troubled themselves with the question of whether a player will improve a team or not, will now be challenged on whether they can draw a direct line between spend on transfer fees and wages, and the club’s bottom line. In other words, is a player’s worth commensurate with his market price?

Our analysis suggests that, in many cases, the answer is no. Take, for example, Philippe Coutinho’s £105m move from Liverpool to Barcelona in January 2018. At the time, we forecast that Liverpool’s performance would decline by around 3 points per season, with the benefit to Barcelona a similar amount. As it happened, Liverpool ended up (much) better off without the Brazilian, and he struggled to make an impact at Camp Nou – but at the time of the deal, few thought the transfer fee to be out of keeping with his talent.

Our statistical assessment that the performance costs and benefits of Coutinho’s move would be relatively modest takes its lead from a simple thought experiment. If a title-winning team earns about 90 points in a season, and a relegated team 35 points, then we know the players in a top team are collectively worth 55 points more than the players in a weaker team.

Over a starting eleven, that’s five points per player. However, title-winning clubs’ replacement-level players – for Liverpool, an Oxlade-Chamberlain, or Fabinho at the time – are far better than starters at relegation-threatened teams, so the drop-off in performance from Coutinho is less than five points. Statistical analysis supported this point.

We can take that analysis a step further and turn points into a monetary value. An examination of the relationship between performance and revenues tell us that a fall of 3 points per season is correlated with a 10 percent reduction in revenue, with of course notable ‘cliff edges’ at European qualification and relegation. To a club with £500 million in revenues, that’s a fall of £50 million – substantially less than Coutinho’s transfer fee and wages. That is, Liverpool received much bigger ‘compensation’ than the anticipated loss in revenue from his departure, and Barcelona overpaid for the anticipated gain.

We are lucky to be in an industry where, with the right analysis, it is relatively straightforward to make this link between input and output, and as clubs become more sophisticated in their decision making, this is bound to impact the market recalibration that will take place over the coming months and years. If large fees are seen to be distasteful in a future world, the least that clubs can do is justify them in the context of the business’ income.

It again also points to the role academies can play in clubs’ survival and revival – if a potential new signing is deemed to be too expensive relative to his likely impact, the odds are that there will be an academy player who provides much better value for money.

A new era for (lower) spending

In decades to come, it is likely that the late 2010s will be seen as a high point for transfer fee spending (or low point, depending on your perspective). All nine of the most expensive transfers in history took place in a 36-month period between 2016 and 2019, each of them at least €100m. More tellingly, only one of them – Kylian Mbappé’s move to PSG – can be considered an unqualified success.

For sellers who have come to depend on fees as a core pillar of their strategy, the likely contraction of the market spells bad news. Fees have served as an invaluable redistribution process of the big five leagues’ massive broadcast revenues, and clubs in these leagues will have to work even harder to market their best young talents. For buyers, the pressure to work smarter has never been higher. Whatever the level, no club wishes to be sucked into a recruitment arms race; every decision will be framed in the context of value.

Covid-19 is forcing a rethinking of every aspect of football finance, and no aspect is more visible than that of transfer fees. They are the mechanism by which fans have grasped the dizzying growth of the economy of the sport, and they will be the mechanism that typifies its austerity.

This article was originally posted in SportBusiness. You can find the original version here.